Repulsively Beautiful: The Convergence of Art and Science

A bacteria-infested Petri dish isn’t where one would expect to find a work of art, but it turns out cell colonies can make masterfully intricate visuals.

Mold has been blamed for the destruction of beauty for millennia–this biotic infestation is often the unfortunate cause of the deterioration of artworks. It is invisible to the naked eye until the right conditions are present. Paintings framed in wood or textile supports are especially vulnerable to fungal growth, since molds consist of microscopic fungi that feed on organic materials. In the presence of humidity, however, the development of mold is particularly favorable. Relative humidity that is over 60-70%, low ambient light, as well as a temperature above 15°C facilitate the dispersal of microorganisms.

In laboratory testing, bacteria harvested from a swab of biological material–blisters, blood, urine, or saliva–is typically grown on a Petri dish filled with agar gel, a gelatin-like substance, in a process known as inoculation. Inoculated plates are then placed into incubators that warm the samples to ideal growth temperatures. This is the method used to induce bacterial growth in order to distinguish between bacteria that are “good,” constituting “normal flora,” and those that are “bad” producing disease or infection. The ability to identify “bad” germs for antibiotic sensitivity is possible through culturing bacteria. Modern technological developments have increased the automation of this process.

Artists have harnessed their knowledge of microbiology and the reproductive cycle of mold to their advantage by intentionally growing it. Rather than worrying about the destructive property of fungus, it can be embraced, creating alluring pieces of art.

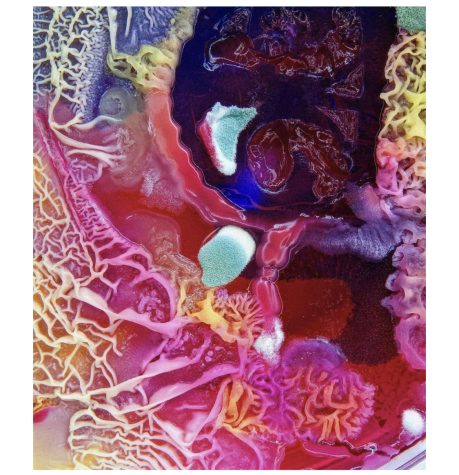

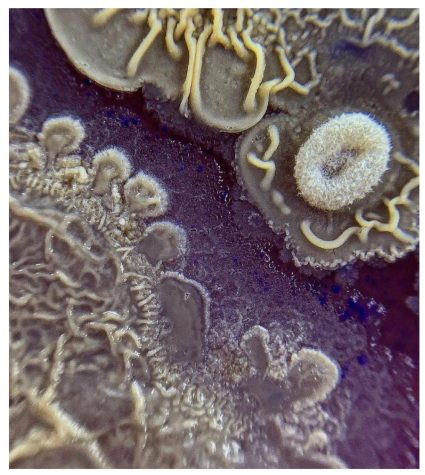

Artist Dasha Plesen combines and develops various bacteria and molds in Petri dishes to capture abstract scenes. Plesen masterfully manipulates the density of nutrients, humidity, lighting, and bacteria type, often using body swab samples of bacteria as her artistic medium. Her art explores textural variety, surreal shapes, and interactions between cell colonies.

“[T]his is the stage, where traditional understanding undergoes a huge upheaval, forming a new version of thinking, doing and collaborating,” explains Plensen.

While neither plant nor animal, fungi still possess the innate capacity for change. Each composition changes periodically, “as a body, breathing, growing and developing, by its stage.” Each dish is fluid in its expression and presentation; one dish can transform into infinite forms. The endpoint appears where the artist deems fit, captured in a photograph.

For such a foul material, the results capture the vastness of a celestial view–all within a microcosmic Petri dish.

Microbial art is not only a recent fad. Alexander Fleming, who discovered the antibiotic properties of penicillin, began creating images using live organisms in 1928. After filling Petri dishes with agar, Fleming used a wire inoculating loop to place microbes with different pigments to “paint” scenes such as houses, soldiers, and ballerinas (among others).

As science continually progresses, who knows what other strange quirks of nature we will be able to transform into something remarkably beautiful.

Manfredi. “Biological Damage Fungi (Mold), Bacteria and Insects.” ARTEnet, 14 June 2021, https://artenet.it/en/biological-damage/.

Magazine, Smithsonian. “Painting with Penicillin: Alexander Fleming’s Germ Art.” Smithsonian.com, Smithsonian Institution, 11 July 2010, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/painting-with-penicillin-alexander-flemings-germ-art-1761496/.

Dasha Plesen [@dashaplesen]. Instagram, 2022, Feb. 2, www.instagram.com/p/CaSxJPfLXif/